Biography of George F. Atkinson

We became curious about Professor Atkinson as we explored his rich scientific materials at the Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium. A short article about him by Torben Russo can be found on the Cornell Mushroom Blog. Here we present a little more about George F. Atkinson—a man who left his stamp on the practice of mycology, but whose personal life and character are elusive now, almost a century after his death.

Origins

Atkinson was born January 26th, 1854 in Raisinville, a small town in Monroe County, Michigan. He remained there with his sisters and his parents, Joseph Atkinson and Josephine Fish, for only 13 years. Then he set out across the country to make his own way in reconstruction-era America. We know from his own accounts that he handled grain on a Mississippi river boat, and spent time in the Black Hills Territory of the Dakotas, driving a four-horse-team-drawn stagecoach during the gold rush of the 1870s. Though he had dreams of becoming a newspaper man, in his own words, he “…did everything as a boy and a man that he could get to do.” Soon he was a grown man who stood well above average at six feet tall, with large, strong, working mans hands.

As he worked and traveled, his ambitions changed and grew, and in 1878, inspired by a sister who had done the same, he used his savings to enroll at Olivet College in Michigan. For the next five years he studied amongst students much younger and less experienced—a man among boys. In 1884 he enrolled as a junior at Cornell University. Atkinson became a student of Cornell’s W.R. Dudley and A.N. Prentiss in botany, H.S. Williams in paleontology, and J.H. Comstock, Gage, and Wilder in animal life (1,3). He also studied English, French, and History. In 1885 he graduated from Cornell as a broadly-trained biologist with a Bachelor of Philosophy degree.

A Career in Biology

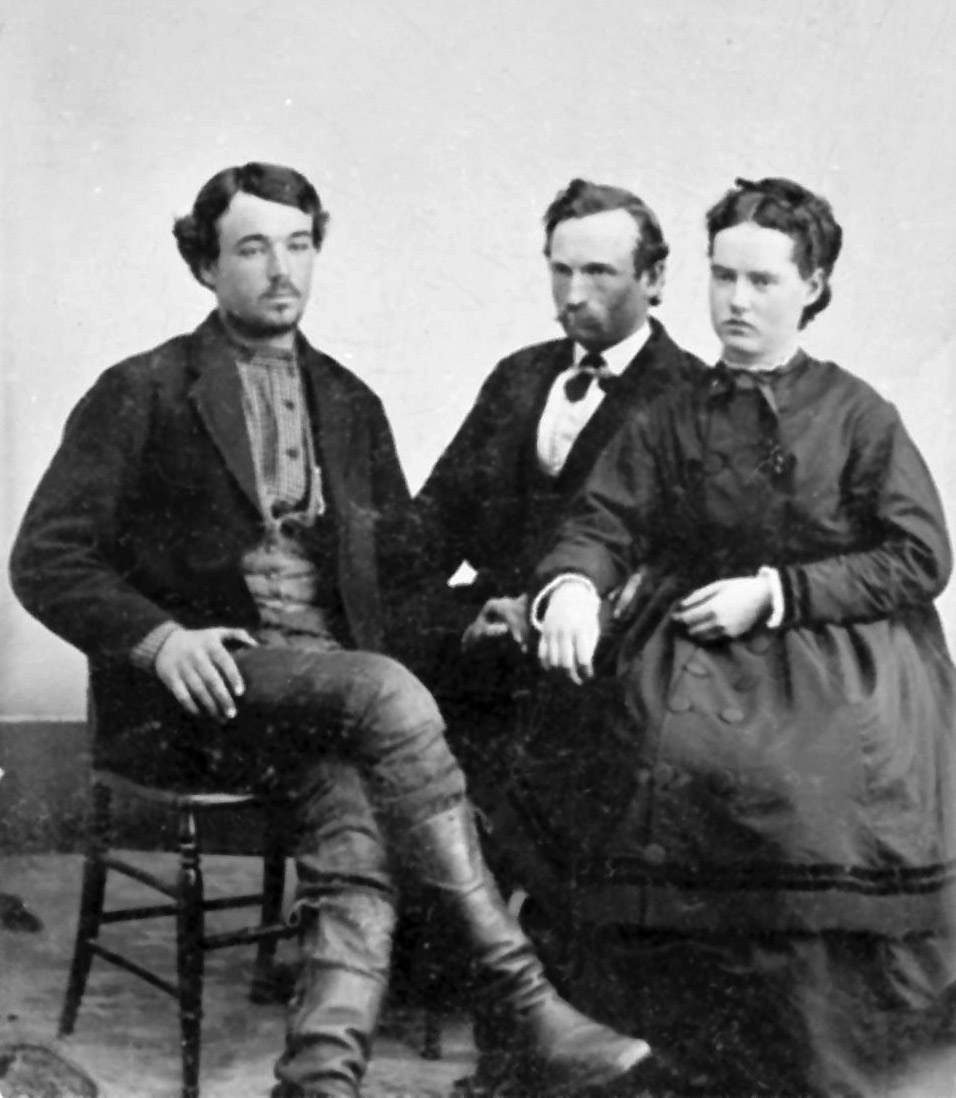

In 1885, Atkinson was appointed Assistant Professor of Entomology and General Zoology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hil. There he met Elizabeth (“Lizzie”) S. Kerr, daughter of the North Carolina State Geologist Washington C. Kerr. In 1887 they were married, and soon had two children, Francis Kerr (b. 1890) and Clara Packard Atkinson (b. 1892).

Between 1885 to 1888, Atkinson published thirteen scientific papers and made numerous contributions to local newspapers, all with a focus on zoology. Five papers focused on spiders—he described new trap-door spidersand studied their behavior, one significant paper documented the birds of North Carolina. His research and teaching skills were praised by Cornell President Andrew D. White (co-founder of Cornell University) and Cornell Professor Burt G. Wilder of neurology and vertebrate zoology (President of the American Neurological Association 1885).

Atkinson at Cornell

In 1892, Cornell University recruited Atkinson as Assistant Professor of Cryptogamic Botany, after Prof. William R. Dudley left Cornell for Stanford University. Within a year he was promoted to Associate Professor, and in 1896, Atkinson became Head of the Botany Department upon the death of Albert N. Prentiss. His attention shifted to mushrooms. His work in plant pathology was delegated to graduate assistants, and eventually to his student Herbert Hice Whetzel,who became first chair of the new department of Plant Pathology in 1907. Atkinson's focus on his work and on fungi was legendary. After lectures he would often instruct assistants to inform him of obligations he might otherwise forget. He spent little time at his home in Cayuga Heights: a 3-acre property he called Laurelwood. He was usually in his lab, as noted by his student Charles Thom: "Atkinson himself was usually there from 7:30 in the morning until 10 at night and was accessible to any worker with a question."

Atkinson's research at Cornell spanned a broad range of topics, focusing mainly on fungi. Though best known for his work on mushroom taxonomy, he also studied plant diseases, made careful studies of Endogone species, studied evening primrose hybridization, and speculated on evolutionary processes. He made careful developmental studies of a number of mushrooms, characterized chytrids, and elucidated the life cycles of plant pathogenic fungi. One paper addressed the intelligence of chytrid zoospores. He described several poisonous mushrooms for the first time, including Amanita bisporigera, the eastern Angel of Death. He rarely took credit via authorship in his students' work. He was an administrator for most of his time at Cornell, which must have limited his time for research, but this is not apparent in his strong publication record. He was also an active and effective teacher, a renowned expert on botany and mycology. He wrote several textbooks for college and high school students of Botany, as well as articles about fungi for popular newsletters.

Atkinson was a pioneer in the use of photography for documenting fungi. He believed it to be a key tool in the standardization of identification and determination. For mushrooms, which dry to shriveled shadows of their fresh selves, photographs are especially useful in documenting living specimens. To his students Atkinson assigned seven steps, enforced by his own strict and thorough approach:

- Bring in all the material—developing fruit bodies, fully-grown and old specimens.

- Color and color changes must be characterized according to Saccardo’s Chromotaxia (a color standard)

- A range of structures must be photographed, using several exposures if needed.

- Complete technical descriptions must be written.

- Spores must be measured and described.

- So also, cystidia and other diagnostic structures.

- The collection site and substrates must be described in detail.

Atkinson and his students collected extensively around Ithaca, New York, and in the Adirondack Mountains, building a large herbarium of Local specimens. He corresponded extensively with Charles Horton Peck (1833–1917), who during his appointment as New York State Botanist described over 2700 species of American fungi, largely in isolation from European studies. Atkinson felt it was important to reconcile the similarities and differences among European and American fungi. To that end, he traveled several times to Europe. 1904 brought him to Uppsala, Sweden, home of the great mycologist, Elias Fries. Fries had passed, but his son Robert Fries, although bedridden at the time, helped Atkinson find sites where Fries' type specimens had been collected, so fresh specimens could be photographed and compared with the old descriptions. Similar work was completed in Stockholm, England, and several years later in France with J.L. Boudier, Réné Maire, and other well-known botanists and mycologists of his time. He taught himself French, and investigated French methods of mushroom cultivation. Thus Atkinson built strong international collections of mushroom specimens, all subject to careful study and photography. His personal notes and scientific photos make his collections very valuable.

Atkinson's Legacy

During his time at Cornell, Atkinson trained a succession of remarkable scientists, who went on to become leaders in their field (the "Dudley lineage" in M. Blackwell's Genealogy of Mycology). Among them, C.H. Kauffman, S.H. Burnham, Bertha Stoneman, C. Thom, F.A. Wolf, W.A. Murrill, Margaret C. Ferguson, Kiichi Miyake, Vera K. Charles, C.W. Edgerton, E.J. Durand, B.M. Duggar, H.H. Whetzel, D. Reddick, and H.M. Fitzpatrick. The last five men went on to become professors at Cornell University.

Endings

Atkinson was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in April 1918, just months before his death in November that year. A few of Atkinson's papers appeared posthumously, a few of which were likely completed by his students from unfinished manuscripts.

At the time of his death, Atkinson was on leave from Cornell, working on research for an extensive illustrated treatment of the mushrooms and coral fungi of North America. With support from Cornell and the US Department of Agriculture, he had already collected and photographed his way south through Maryland, North Carolina, and Florida. In the late Fall he traveled to Washington State, which is where he fell ill at the peak of the pandemic of Spanish Influenza that was sweeping the planet, utimately killing more than 3% of the global population.

His Landlady, Mrs. Clother, reported that he'd been working very hard, staying up late, taking photographs and notes. On November 5th, 1918, Atkinson had returned from collecting around Spanaway Lake and seemed fine. But the next morning Mrs. Clother found his door locked—strange, since he had requested his room be made up at 7 AM. Knocking, she found he was sick. A doctor was arranged, who advised hospitalization. Before leaving, Atkinson gave stern instructions to be careful of his collected materials and other equipment, worried more about his work than his health. Seven days later, after periods of delirium and voicing numerous concerns about his fungi, Atkinson died. He was 64 years old, and at the height of his academic career.

Though his planned ten volumes were never completed, his work lives on via his publications, and especially in his collection, notes, and photographs, housed here at the Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium.

References and Further Reading

See our bibliography of Atkinson's scientific papers.

- Richard P. Korf. 1991. An historical perspective: Mycology in the departments of Botany and of Plant Pathology at Cornell University and the Geneva Agricultural Experiment Station. Mycotaxon 40: 107-128.

- Fitzpatrick, H.M. 1919. George Francis Atkinson. Science, N.S. 49 (1268): 371-372.

- Raper, K.B. 1965. Charles Thom, 1872-1956. [PDF file]

- Thom, C. 1956. George Francis Atkinson, 1854–1918. [PDF file]

- The Atkinson Archive at Kroch Library Rare and Manuscript Collections [Archives 47-1-3692], Cornell University.

Acknowledgements

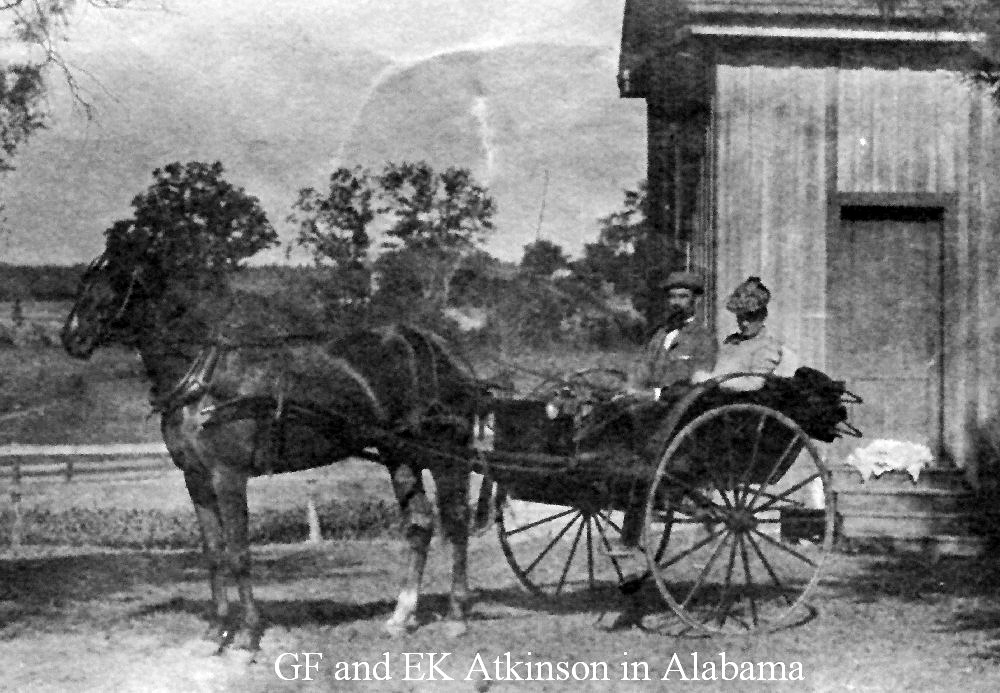

This short biography was compiled by Torben Russo, Robert Dirig, and Kathie Hodge, with help from many people. We are especially grateful to G.F. Atkinson's grandson and great-granddaughter, William C. (Bill) Atkinson and Holley Atkinson, for sharing the family photographs presented on these pages. Richard P. Korf has been an inspiration to us, and we appreciate his historical articles and tales of Cornell history. The Staff at the Cornell University Archives have assisted us in finding Atkinson's correspondence.

"Mushrooms, too, have a story to tell." G.F. Atkinson, 1901.

| ATKINSON MILESTONES | |

|---|---|

| 1854 | Born on January 26 in Raisinville, Michigan |

| 1885 | graduated from Cornell with a Bachelor of Philosophy degree at the age of 31 (view diploma) |

| 1885-1888 | Assistant Professor of Entomology and General Zoology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| 1888 | Professor of Botany and Zoology, and Botanist to the Experiment Station in the University of South Carolina at Columbia. |

| 1887 | Married to Elizabeth ("Lizzie") S. Kerr |

| 1889 | Professor of Biology, Alabama Polytechnic Institute, of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama, and Biologist for the Experiment Station in Auburn |

| 1890 | Assistant Professor of Cryptogamic Botany, Cornell University |

| 1896 | Head of the Botany Department, Cornell University |

| 1918 | Elected to the National Academy of Sciences (view award) |

| 1918 | Died of Spanish Influenza on November 14, while in Washington state to collect fungi |